Kriangsak Koopattanakij/iStock via Getty Images

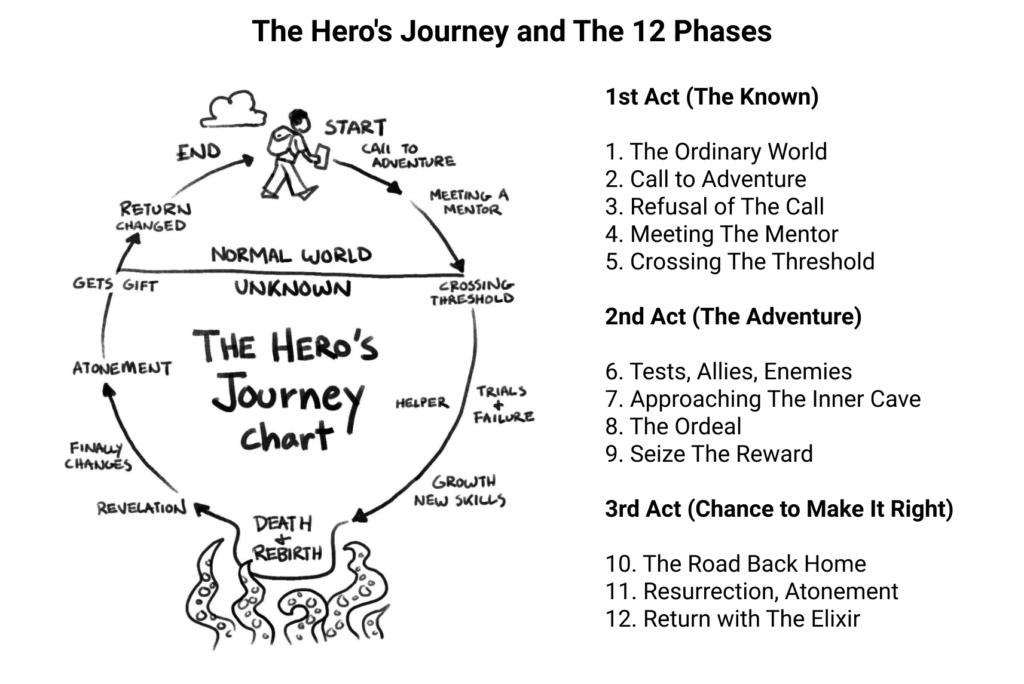

Have you ever heard of the hero’s journey?

In 1871, anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor observed a common pattern in literature and mythology.

The main protagonist:

- Goes on an adventure.

- Faces trials and errors.

- Wins a decisive crisis.

- Returns home transformed.

You can find this pattern in novels, movies, and TV shows, from Homer’s Odyssey to George Lucas’ Star Wars.

Hero’s journey structure (Kanbanazie)

I often describe investing as a “journey” requiring its fair share of trials and failures.

The investing journey requires us to experiment, learn painful (costly) lessons, and ultimately change for the better (hopefully).

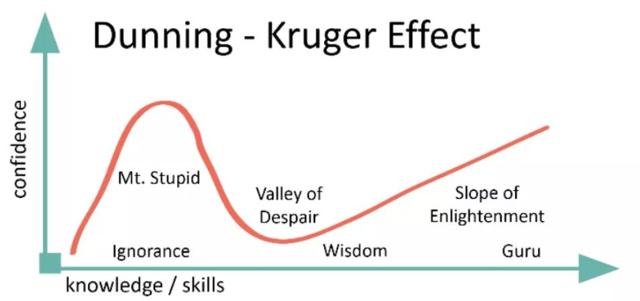

The main challenge? There is no way to really know what we have yet to learn. As a result, we tend to poorly assess our level of competence, also known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Dunning – Kruger Effect (Marketcalls)

We are all our own heroes, each of us at different stages of our journey.

Some of us are still dabbling with a brand new brokerage account.

Others may already live off their investment portfolio and feel enlightened.

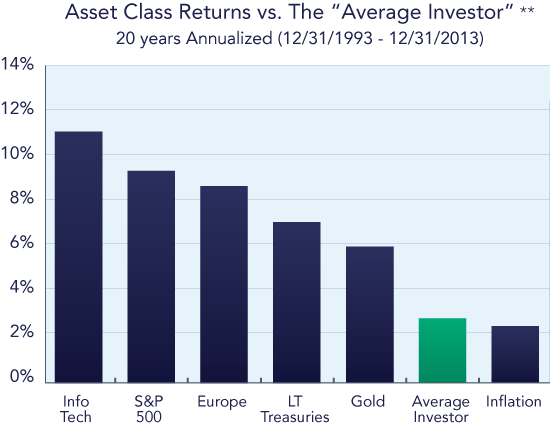

Collectively, we are terrible at investing. As illustrated below by the data from Richard Bernstein Advisors, the average investor can barely keep up with inflation.

20-year annualized returns by asset class (Richard Bernstein Advisors)

I like to look at the sum of our learning experiences as a collection of investing “secrets” that require time and effort. The way we invest at any given time results from epiphanies accumulated over the years.

I call them secrets because they remain elusive to most investors, as illustrated by the chart above.

So today, I want to cover ten essential investing secrets I have gathered over the years. Some might appear semi-controversial because they challenge the way many people think.

I hope you’ll take the time to share your own learnings with me in the comment section.

Let’s dive in.

1) The Power Law Governs Returns.

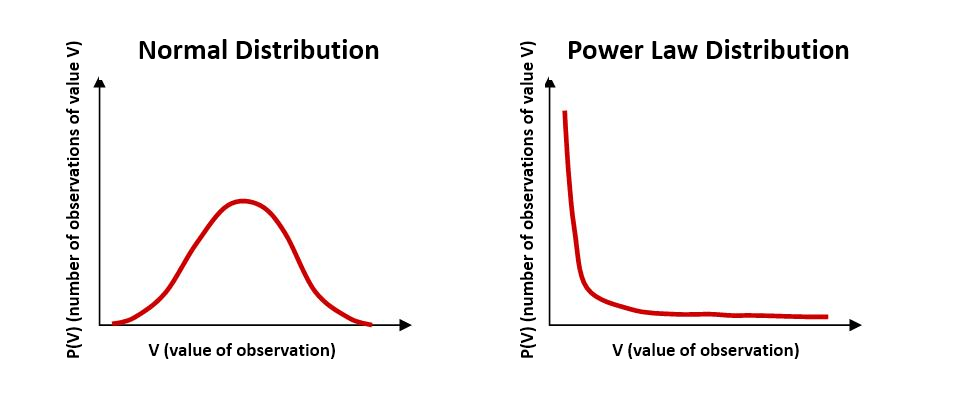

The first secret is about statistics and probability.

A normal distribution of outcomes, also known as the Gaussian distribution or the bell curve, shows that extreme scenarios (also called outliers) tend to happen less.

If we use the example of the roll of two dice, the distribution is centered around the number seven. The further away you move from the number seven, the less likely the outcome is. Other normal distribution examples include the distribution of height or shoe size.

But in investing, another distribution of outcomes comes into play.

It is called the power law, also known as a Pareto distribution.

You have probably heard of the Pareto Principle, also called the 80/20 rule. Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto developed this concept in 1906. Pareto realized that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. He also noticed that 20% of the pea pods in his garden were responsible for 80% of the peas.

Pareto states that roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of the causes (also called the “vital few”). This principle is observed across economics, computing, and sports:

- 80% of the GDP is in the hand of roughly 20% of the population.

- 20% of a company’s products generate 80% of the revenue.

- Fixing 20% of the most-reported bugs fixes 80% of the related crashes.

The list goes on.

The power-law distribution involves that:

- Small outcomes are very likely.

- Large outcomes are less likely.

- The distribution decays slowly (also called “fat tail”).

Normal vs. Power Law Distribution (Leadertainment)

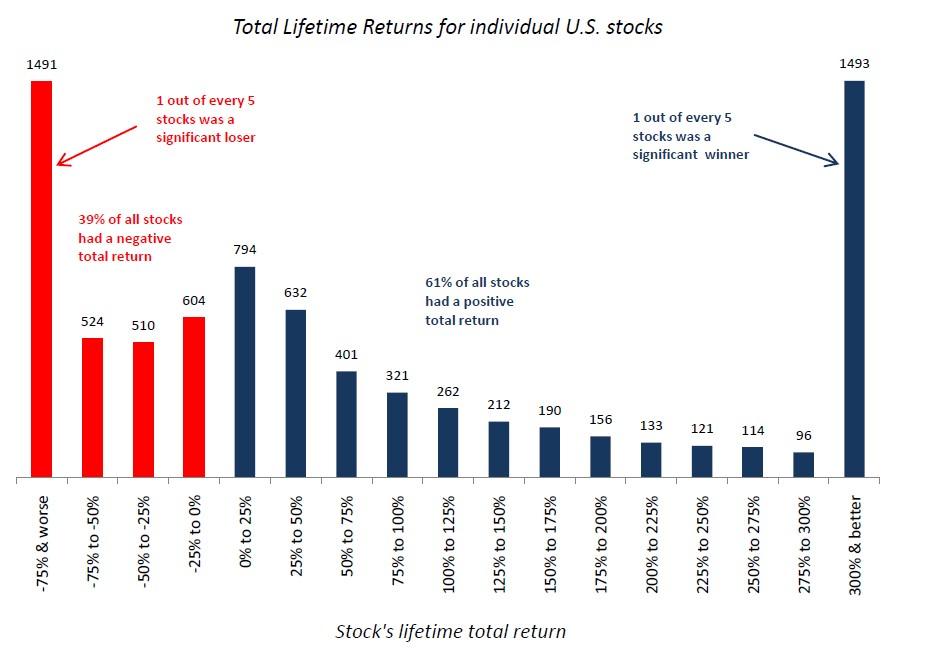

Blackstar Funds reviewed the historical distribution of 8,000 stocks trading on the NYSE, AMEX, and Nasdaq over decades (1983-2006). During this period, 25% of the stocks were responsible for all gains. As you can see, the power-law distribution would apply to a large stock sample like an index fund.

NYSE, AMEX and Nasdaq over decades (1983-2006) (Blackstar Funds)

In his book Zero to One, Peter Thiel explains:

We don’t live in a normal world; We live under a power law.

He elaborates:

The biggest secret in venture capital is that the best investment in a successful fund equals or outperforms the entire rest of the fund combined.

The power law should set your expectations for your portfolio performance. O To illustrate, the top 20% of your investments will likely represent 80% of your returns. Once you understand this distribution, you will start looking at your best-performing investment with the attention and care they deserve.

If you let your portfolio perform without rebalancing, your few biggest winners will represent most of your returns over time.

I started the App Economy Portfolio in 2015 and can attest to this distribution. Today, about 80% of my gains come from less than 20% of my investments.

I should clarify that the power law would only apply to a portfolio that grows organically without active rebalancing. VC portfolios look like this because they make illiquid investments with years to compound.

In 1984, Robert G. Kirby introduced the idea of the Coffee Can portfolio. In his white paper, Kirby explains:

You can make more money being passively active than actively passive.

Being passively active is an extreme version of the good old “buy and hold” approach. In short, Kirby is preaching the idea of never selling.

- The active part is your buying strategy – your investment selection.

- The passive part is your behavior – that is, not to sell for as long as you possibly can. Sitting on your hands, if you will.

The Coffee Can illustrates the passively active approach. Kirby explains:

The Coffee Can portfolio concept harkens back to the Old West, when people put their valuable possessions in a coffee can and kept it under-the mattress. That coffee can involved no transaction costs, administrative costs, or any other costs. The success of the program depended entirely on the wisdom and foresight used to select the objects to be placed in the coffee can to begin with.

Assets are picked for their inherent quality and left alone over an extended period. An obvious benefit to this approach is that you will likely think twice before adding a position to the portfolio.

The Coffee Can portfolio is, to a large extent, part of Warren Buffett’s strategy. He likes to say that his favorite holding period is “forever.” This approach has generally implied high concentrated bets. It certainly worked out well for him. As of August 2022, Buffett had 73% of his equity portfolio at Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A) (BRK.B) in his five largest holdings:

- Apple (AAPL) 42%.

- Bank of America (BAC.PK) 10%.

- Chevron (CVX) 7%.

- The Coca-Cola Co. (KO) 7%.

- American Express (AXP) 7%.

Kirby illustrates the positive results of this strategy with the portfolio of a client he had worked with for over a decade. The client had invested around $5,000 in his wife’s portfolio for each of Kirby’s purchase recommendations without selling. The result, after decades, was a portfolio with several small positions around $2,000, a few large ones that had grown to $100,000, and one that had returned over $800,000.

Over an extended time, a portfolio that isn’t rebalanced or tinkered with is going to get heavily concentrated. If you are successful with this strategy, you will end up with an odd-looking portfolio with a few winners generating most of the alpha. Kirby’s friend would have never generated such returns if he had regularly re-examined and rebalanced his portfolio, as taught in most modern corporate finance classes.

If your portfolio becomes highly concentrated over time, it will have necessarily been fueled by a selection of alpha-generating investments. Your portfolio concentration would result from its performance, not your blind conviction.

If you embrace a Coffee Can approach, essentially letting your winners run, a single investment will likely return more than all your other investments combined. It might sound like a romantic idea at first, but it’s the natural result of the world we live in, a world governed by the power law.

An essential aspect of the passively active approach is that you only need to be right once. There is no market timing, no need to check your brokerage account every other minute. Instead, you make an investment decision and leave it alone for many years.

After all, this is how Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), Amazon (AMZN), and Alphabet (GOOG) now represent 20% of the S&P 500 (SPY).

2) Volatility is the cost of admission.

Historically, the market has gone up over time, with an average 10% annual return from 1926 to 2021 for the S&P benchmark (VOO), and 74% of the years were positive.

- A Bull Market is measured from the lowest close reached after the market has fallen 20% to the next high.

- A Bear Market is defined as the index closing at least 20% down from its previous high close. Its duration is from the previous high to the lowest close reached after it has fallen 20% or more.

Here is the historical frequency of pullbacks identified since 1928:

| Market drawdown | Historical Frequency |

| 10% | Every 11 months |

| 15% | Every 24 months |

| 20% | Every four years |

| 30% | Every decade |

| 40% | Every few decades |

| 50% | 2-3 times per century |

As we go through a turbulent time in the market, remembering that market drawdowns are part of the investing process is essential.

There are two essential dynamics:

- The stock market goes up much more than it goes down (several bull markets have lasted more than ten years, at more than 17% average annualized return).

- When it goes down, it goes down fast and sharply (bear markets have lasted less than three years, from -22% to -83%).

Morgan Housel puts it perfectly:

The whole reason stocks tend to do well over time is because they make you put up with stuff like this. It’s the cost of admission.

A feature, not a bug.

A bull market might seem like a steady path up and to the right, but volatility is present in all market conditions. Red days and moments of doubt are ubiquitous, even through bull markets. Knowing more about the stock market history can help you put the current market in context and keep a long-term perspective.

A volatile market is not a reason to sell. It’s just the way the market works.

Charlie Munger sums it up:

If you’re not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century … you deserve the mediocre result you’re going to get compared to the people who do have the temperament, who can be more philosophical about these market fluctuations.

3) Expanding our time horizon reduces risk.

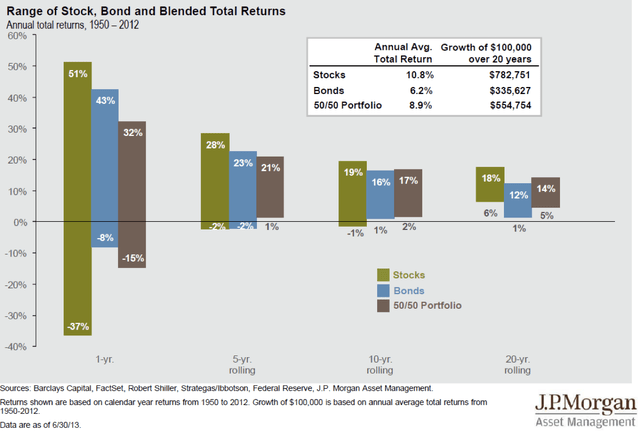

The chart below shows the range of annual returns for stocks and bonds based on the holding period. Over a 1-year timeframe, the range of outcomes can be extreme, from a loss of -37% to a gain of 51%. However, the longer the time horizon, the less likely you will lose money. Over a 20-year period, investing in stocks always yields positive returns. Even the worst period tested had a 6% average annual return.

Range of Stock and Bond Returns (JM Morgan Asset Management)

Since stock returns over one year are essentially a coin flip, expanding our time horizon is critical. Just like in a video game, if there is such a thing as an “easy mode” in investing, it’s for those who choose to invest over a longer time frame without predicting market tops and bottoms.

Another benefit of this approach is to start behaving like a business owner. Legendary investor Li Lu of Himalaya Capital Management explained:

We view ourselves primarily as owners of businesses, and typically hold our positions for a very long time with very low turnover.

When you invest with a multi-year time horizon, you are more willing to give management the benefit of the doubt and let the story play out.

And that’s great news! Because success is not linear. And no matter how great your next investment is, it will underperform at some point. I discuss this topic in my article about What It Takes To Hold Winners.

Hedge funds and Wall Street analysts are focused solely on quarter-to-quarter performance. Fortunately, one of the individual investor’s unfair advantages is to be able to work on a different timeframe.

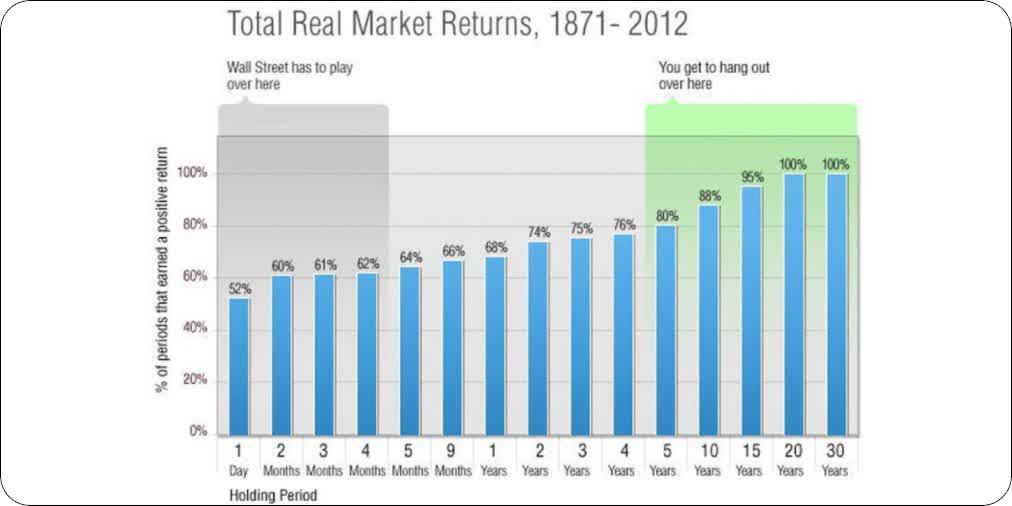

To illustrate, the graph below shows real market returns based on the holding period. It’s not hard to see why you would want to ignore Wall Street’s obsession with the next few months and embrace a holding period of five years and beyond.

Total Real Market Returns, 1871-2012 (Morgan Housel)

We get to play on our own terms and improve our odds of success.

Expanding your time horizon removes the need to do well “now” and eliminates the need to have perfect timing in and out of a stock.

4) Only fundamentals matter in the long run.

An entire world opens up if you are willing to expand your time horizon.

While stocks regularly rise or fall based on the day’s headlines, the dynamic changes as we look at a longer time frame.

I tried to encapsulate this idea in the tweet below.

An easy way to see how price eventually follows fundamentals is to look at charts showing price and EPS (earnings per share) over time. Below is an illustration with Alphabet (GOOG) (GOOGL) since 2004.

Staying focused on business performance is more critical than ever in the current environment. Our emotions are tested in real-time, and it can be challenging to keep a cool head.

The human brain is not meant to handle uncertainty very well. Our instinct is a protective mechanism. While it can benefit us when facing danger stranded on an island, it can be counter-productive for our investing approach.

In his letter “The Value of Not Being Sure,” Seth Klarman discussed the challenge of not responding to the vicissitudes of the market:

If you see stocks as blips on a ticker tape, you will be led astray. But if you regard stocks as fractional interests in businesses, you will maintain proper perspective. This necessary clarity of thought is particularly important in times of extreme market fluctuations.

It can be tough to take the 30,000-foot view when reading financial news feels like a slap in the face every morning. Stock price movements will make you second-guess yourself. And with so many opinions on the web running counter to your strategy, you need to build your own conviction. I cover this topic in more detail in my article Know What Game You’re Playing.

We are wired to judge our investments by the stock price performance in the minutes, hours, or days following our purchase, even when it shouldn’t matter.

Warren Buffett points out that only fundamentals matter over time:

People buy a stock and they look at the price next morning and they decide to see if they are doing well or not doing well. It is crazy. They are buying a piece of the business. That is what Graham – the most fundamental part of what he taught me. You are not buying a stock, you are buying part ownership in a business. You will do well if the business does well, if you didn’t pay a totally silly price. That is what it is all about.

There are many ways to stress test your motivation and ensure you invest with the right intentions. For example, Buffett often suggests that investors should buy a stock as if they bought the entire business. Only a company that can eventually return cash to shareholders should be considered.

Conversely, those following the greater fool theory will buy stocks solely because they believe they can quickly sell them off at a higher price, without regard for quality. Their time horizon will be infinitely shorter.

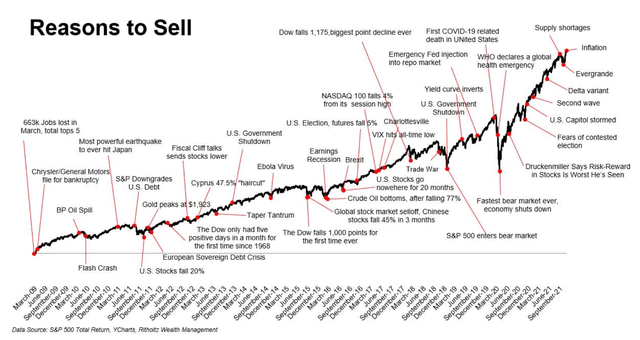

5) There is always a reason to sell.

There is always a new doom and gloom scenario to consider.

Pockets of mania lead to fresh articles about the bubble du jour. From Brexit to Trade Wars to inflation, terrorist attacks, and bear markets of all kinds, it’s as if the end of the world is always around the corner.

Thankfully, there rarely is a call to action if you are a disciplined investor.

The best course of action for the past century was to remain invested through thick and thin and stay the course.

Reasons To Sell (Ritholtz Wealth Management)

If you invest with a multi-year time horizon, you can skip macro headlines and focus on the businesses you’re investing in (or whatever it is you enjoy in life!).

Additionally, you can always find a justification to sell a stock you own.

Success is not linear. Even the best-performing businesses in the world have a series of bad quarters at some point. If you look long enough, you’ll find a reason to part ways with your shares, probably at the worst possible time.

I’ve found that the best way to alleviate this challenge is to document my bull case in detail. As long as the original thesis is intact, there is no call to action.

6) Macro Predictions Should Be Ignored.

By not trying to predict interest rates or any other macro factor, you can stay focused on the business fundamentals, which are ultimately the only driver that will matter over multiple economic cycles.

The market swings like a pendulum. It overshoots to the upside and the downside in unpredictable ways. Anybody who believes they can predict what will happen next is either a beginner or a charlatan. Predicting future market movements is a fool’s errand.

The macro-environment is on everyone’s mind at the moment.

We are facing a wide range of outcomes:

- Has inflation peaked?

- How will the war in Ukraine escalate?

- How many rate hikes will occur in 2022?

- How will earnings and guidance be impacted?

- Will there be a recession in the coming two years?

The answers to these questions will affect the next few quarters, and investors will adjust their expectations.

The truth is, there will always be something to worry about.

The market tends to be forward-looking, factoring in good or bad news long before they materialize.

- You can’t predict the economy.

- You can’t predict with certainty what the Fed will do next.

- Even with perfect information on the above, you still couldn’t predict how the market would react. So, why bother?

Reading about the macro environment can only help with two things:

- First, put the current market in historical context.

- Second, set your expectations appropriately.

Your time and head space should focus primarily on information and sources anchored in what is knowable: past performance, company statistics, trend analysis, business analysis, market research, or best practices.

For more on this, I recommend Howard Marks’ recent memo,” I Beg To Differ.”

You’ll have to do something better than the crowd to beat the market. And it generally comes down to two things:

- First, what do you pay attention to?

- Second, how does it influence your decision process?

Unfortunately, most readers care first and foremost about the outlook for the macro environment. In short, everyone wants to know what will happen next.

Howard Marks explains:

All the discussions surrounding inflation, rates, and recession falls under the same heading: the short term. And yet:

- We can’t know much about the short-term future (or, I should say, we can’t dependably know more than the consensus).

- If we have an opinion about the short term, we can’t (or shouldn’t) have much confidence in it.

- If we reach a conclusion, there’s not much we can do about it – most investors can’t and won’t meaningfully revamp their portfolios based on such opinions.

- We really shouldn’t care about the short-term – after all, we’re investors, not traders.

He explains how we have to think and invest differently to generate alpha. And why the best form of contrarianism is to invest on a different time horizon than most of Wall Street.

[…] my suggestion to you is to depart from the investment crowd, with its unhelpful preoccupation with the short term, and to instead join us on the things that really matter.

7) Your behavior drives your returns.

We are all, to a certain extent, portfolio managers.

Whether you do it yourself or someone else handles it on your behalf, your portfolio is the result of thousands of decisions over a lifetime. Your returns are shaped by your time horizon, asset allocation, style, geography, size, sector, company selection, and more.

But the single greatest factor that will determine your portfolio’s returns is no other than your temperament.

Buffett explains:

Success in investing doesn’t correlate with IQ. Once you have ordinary intelligence, what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people in trouble investing.

We take pride in deep research or detailed valuation methods, but they can be rendered useless with the wrong temperament. There’s no amount of reading and self-help that can sufficiently address our flaws as human beings.

Even with the best intentions in mind, investors eventually make mistakes that can make their portfolio returns vanish. They come across the idea of a lifetime and decide to bet the farm on it. They anecdotally invest in companies just because a coworker mentioned it at the water cooler. They sell 50% of their stock portfolio because talking heads on CNBC suggested that a downturn is coming soon.

Risk-averse investors think they are taking too much company risk as soon as a stock reaches 5% of their portfolio. Yet, many are willing to take a 30-year mortgage to buy a single-family home with a down payment representing the vast majority of their net worth.

One of the most underrated aspects of investing is portfolio suitability.

Since staying the course is critical to your investing success, finding a portfolio that matches your predisposition is paramount. We all have circumstances leading to a different perspective.

As perfectly put by Adam Smith in The Money Game:

If you don’t know who you are, (the stock market) is an expensive place to find out.

8) IPO means It’s Probably Overpriced.

Ken Fisher famously coined the phrase “IPO means It’s Probably Overpriced.”

The data seems to confirm it. Phil Mackintosh of the Nasdaq Economic Research found that three years after going public, almost two-thirds of IPOs between 2010 through 2020 underperformed the S&P 500 by more than 10%.

Distribution of IPO returns post-IPO (FactSet, Nasdaq Economic Research)

I have previously covered five tips to generate alpha with IPOs:

- Set reasonable expectations based on what you are getting into;

- Listen to the first couple of earnings calls before buying;

- Only nibble at it in the first year;

- Let the investment tell its story over several years; and

- Don’t agonize over price fluctuations.

These five tips can keep you away from a lot of losers. When compared to companies of similar size, IPOs underperform, particularly from six to 24 months after the IPO date. It could be explained by the selling pressure around the end of the lock-up period. As a hot IPO’s novelty wanes, expectations return to earth, and so does the stock price.

As explained in my article, you can put the odds in your favor by:

- Focusing on larger IPOs.

- Companies backed by VC money.

- Avoiding the lock-up period.

Avoiding the first few months after an IPO is common-sense investing, but it’s even more essential when the number of new IPOs is abnormally high. In today’s market, you would have to include SPAC-IPOs as well.

I discussed the inherent risks related to red-hot new IPOs in my article about 3 investments I would avoid at all costs at the end of 2020. It turns out we were a few months away from a market top.

New investors rarely go “all-in” on a mature business with years of track record. However, they do so with brand new public companies under the allure of novelty.

It’s an easy pitfall to avoid once you understand the odds. Buyer beware.

9) Timing the market is futile.

One of the biggest mistakes novice investors make is trying their luck at market timing. They think that they can anticipate not only economic trends but also the corresponding effect on stock prices.

Anyone who has been exposed enough to financial literature understands that market timing is a hazardous hobby. One that can eat away at your long-term returns very fast.

There are so many reasons why attempting market timing is a poor idea:

- You need to be lucky on both the exit and the re-entry.

- You are competing with institutional investors that use supercomputers and complex data algorithms.

- Your odds of success are very thin, with significant upswings and downswings usually happening in tandem.

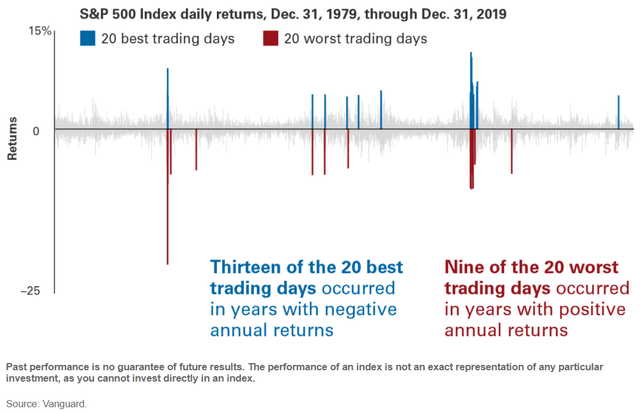

The futility of timing the stock market is illustrated by its best and worst days happening close together. Those who claim they have avoided the worst days will omit that they missed the best ones.

Best and worst trading days (Vanguard)

Those who try to time the market to avoid a red year can easily jeopardize their long-term performance simply by being out of the market at the wrong time. Even missing a few good days out of an entire decade can annihilate most of your returns.

If you are out of the market and it keeps going higher, at what point do you recognize you were wrong and get back in? I touched on this in my article covering 6 Mistakes To Avoid in a frothy market.

Many commentators brag online, claiming they have sold their stocks “at the top” or recently bought “at the bottom.” But how many times have they been wrong before they were right? What are their annual returns over a lifetime of investing?

Over the long term, stocks will appreciate and follow GDP growth. You are guaranteed to lose if you are out of the market long enough.

I avoid all forms of market timing and invest a fixed amount every month.

According to a research note from Bank of America Securities, the average time for the market to get back to where it was after a drawdown of 20% or more is 4.4 years. As a result, most advisors recommend investing in equities only if you intend to hold your investment for the next five years.

Even assuming you have terrible timing and invest right before a bear market, you will still have an excellent chance to be back in the green after five years.

10) Successful investing takes time.

As explained by Charlie Munger:

It’s waiting that helps you as an investor, and a lot of people just can’t stand to wait. If you didn’t get the deferred-gratification gene, you’ve got to work very hard to overcome that.

Two main factors drive our investing success:

- The money we put to work.

- The number of years we keep it invested.

A fundamental part of the success of an investment portfolio is how early in your life you start and how much you contribute to it.

Until you have been investing for 20+ years, the amount you save probably matters more than your returns.

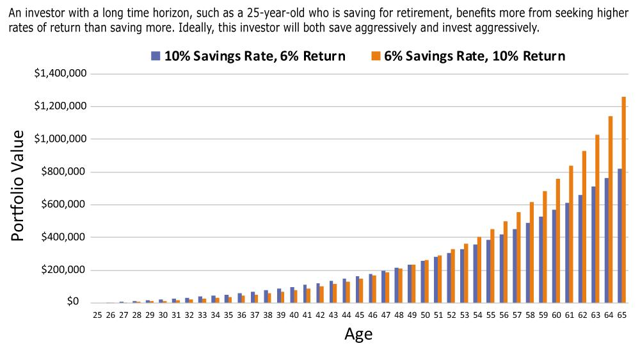

I came across the graph below via Meb Faber, showing how two types of portfolios would create value over time:

- Portfolio A = 10% Savings Rate, 6% Return

- Portfolio B = 6% Savings Rate, 10% Return

Using the example of someone who starts investing at 25, the investment return starts to matter more than the savings rate after 25 years of investing.

Savings vs. Investing (Meb Faber)

As you can see, you should try to save just as much as you are seeking alpha. Most of your portfolio value is likely to come from your savings rather than your returns (at least for a couple of decades).

In the book, the Millionaire Next Door, Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko discuss the concept of the “prodigious accumulator of wealth.” It’s not about hoarding pennies under your mattress. It’s about paying yourself first and taking risks when they are worth the reward.

Success in the investing game depends on our willingness to take care of our future selves:

- Spend less than we earn.

- Invest what we save diligently.

- Let the power of compounding do its magic for years on end.

Patience is an essential virtue of the investor. Probably the most precious one.

As American economist Paul Samuelson wrote:

Investing should be more like watching paint dry or grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas.

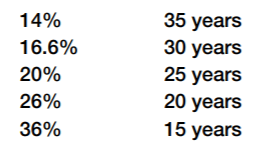

Thomas Phelps, the author of the book 100 to 1 in the Stock Market, has provided valuable lessons to understand the power of compounding better.

A 100-bagger is a stock that returns 100 times your initial investment. That means a $10,000 investment would turn into $1 million. You wouldn’t need to find many to achieve your investing goals.

If you ever hope to have a 100-bagger in your portfolio, you might wonder how long it would take to get there. The higher the compound annual growth rate, the fewer years you need to get there. It’s simple math. Phelps has a table in his book that lists the annual returns and how many years it would take before you get a 100-bagger:

Time to have a 100-bagger (Thomas Phelps)

If you hold a stock compounding at 20% annually for 25 years, you return 100 times your money. But if you hold it for 10 years, you only return 5 times your money.

Even assuming you have found the investment idea of a lifetime, you would still need decades to see the story come to fruition.

Let’s assume that you already own such stock in your portfolio. What are the odds that you will let the story play out over 20 years or more?

Probably thin.

Long holding periods are not simply a preference. They are an absolute necessity to achieve life-changing returns.

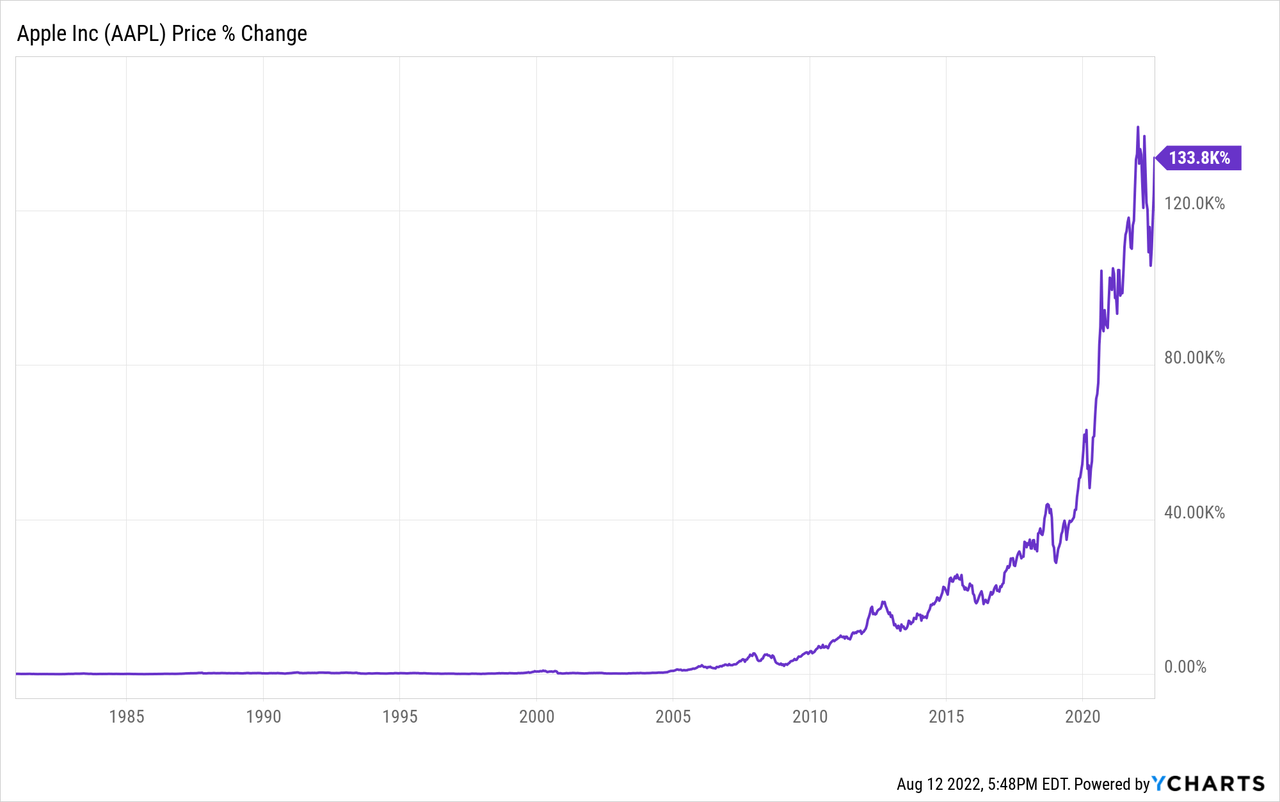

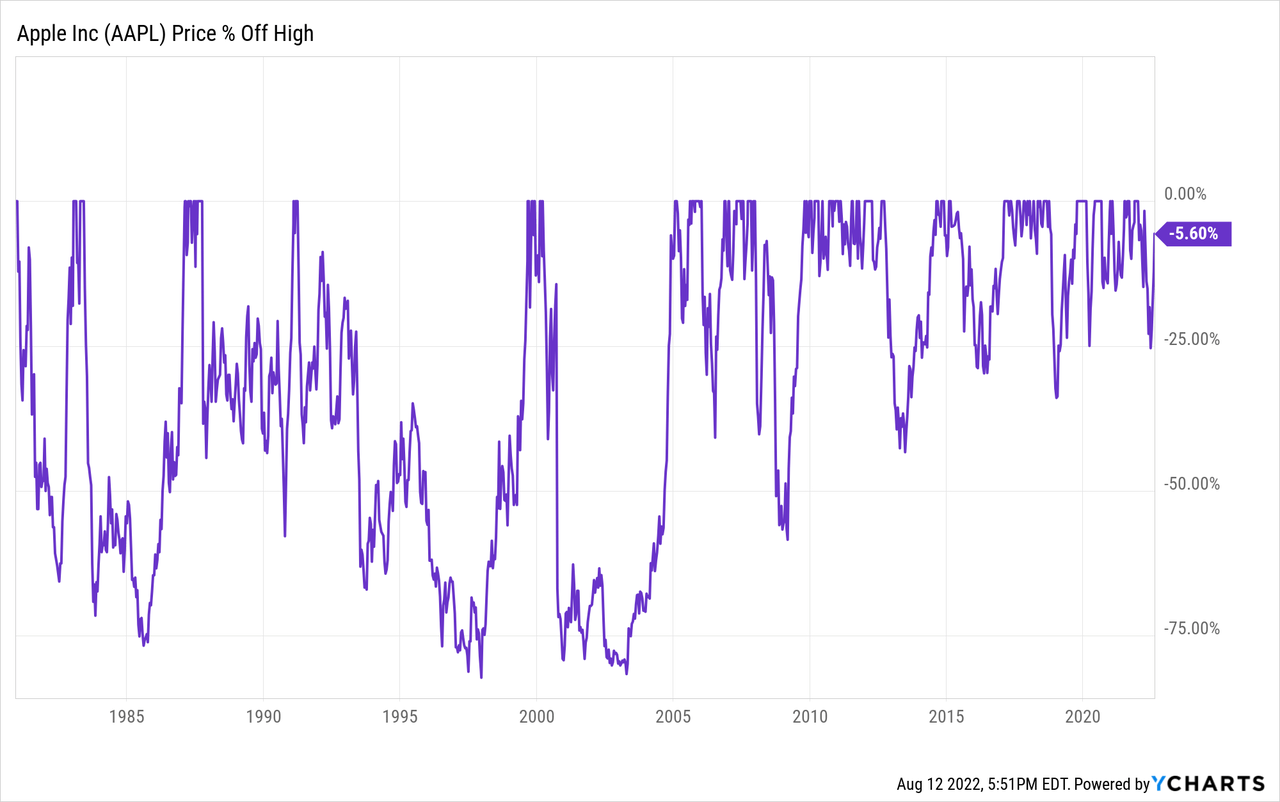

A company like Apple (AAPL) has been a 1,000-bagger in the past 40 years.

But to enjoy such a ride, you had to be able to handle a dozen sell-offs of 25% or more, including three sell-offs of 80%.

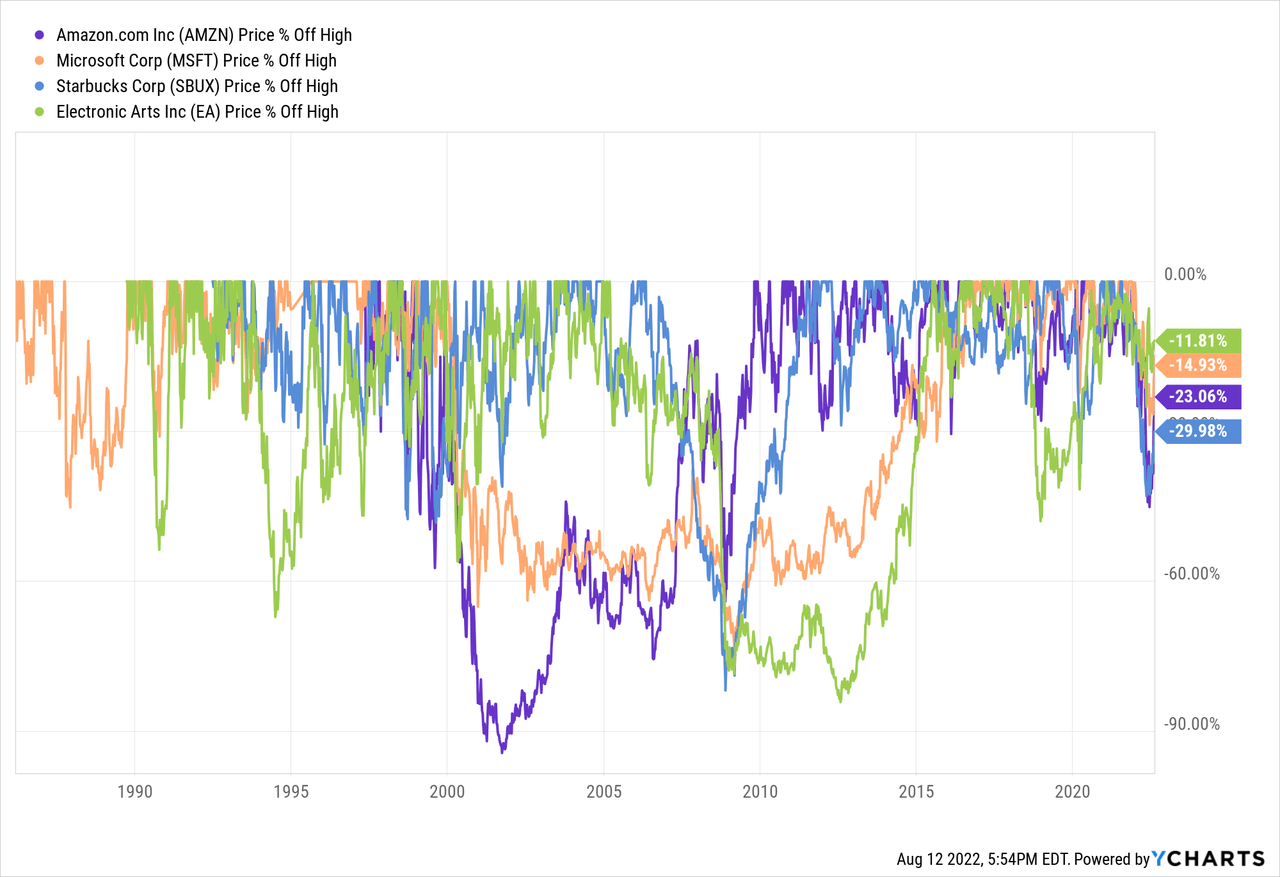

And Apple is far from being the only company in this category. The likes of Amazon (AMZN), Microsoft (MSFT), Starbucks (SBUX), and Electronic Arts (EA) are all examples of well-known companies that returned far more than 100x over the years for those who could cope with more extreme drawdowns than I can count in the chart below.

Holding one of these companies over the past three decades would have likely created life-changing returns in your portfolio.

And the same logic applies to the market benchmark. The S&P 500 (SPY) grew more than 7x over the past 30 years, with two drawdowns of more than 40% in the 2000s.

In short, the power of compounding needs an extended amount of time to really shine. So getting lucky is not enough. You also have to filter out the noise, be a reluctant seller, and give it time.

I’ll leave you with one more Buffett quote:

Someone is sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago.

Bottom Line

In summary:

- The Power law governs returns.

- Volatility is the cost of admission.

- Expanding our time horizon reduces risk.

- Only fundamentals matter in the long run.

- There is always a reason to sell.

- Macro predictions should be ignored.

- Your behavior drives your returns.

- IPO means It’s Probably Overpriced.

- Timing the market is futile.

- Successful investing takes time.

These epiphanies may seem obvious to you.

You might think they don’t qualify as “secrets.”

But they do.

Otherwise, how can we explain the plethora of books and articles focused solely on short-term trading, macro predictions, or market timing strategies? How could we explain that the average investor continues to underperform the market, decade after decade?

The 10 points above remain elusive to many market participants who decide to play the investing game with the deck stacked against them.

I hope some readers will have the same a-ha moments as I did when I first came across these concepts.

What about you?

- What investing secrets have you learned in your investing journey?

- Which ones have changed how you invest?

- What would you change if you could go back in time?

Let me know in the comments!

Techyrack Website stock market day trading and youtube monetization and adsense Approval

Adsense Arbitrage website traffic Get Adsense Approval Google Adsense Earnings Traffic Arbitrage YouTube Monetization YouTube Monetization, Watchtime and Subscribers Ready Monetized Autoblog

from Investing – My Blog https://ift.tt/bdmjNe4

via IFTTT